Dale Fisher

Dale Fisher (born in Gundagai, New South Wales) is widely regarded as one of Australia’s pioneering custom car builders. Active from the 1950s through the 1980s, Fisher became known for his ingenuity in transforming ordinary production cars into highly individualized custom vehicles. Often referred to as “Australia’s George Barris,” Fisher completed more convertible conversions from two- and four-door cars than any other individual in the country, influencing a generation of Australian customizers and automotive enthusiasts.

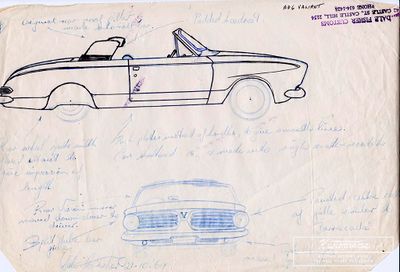

According to his son, Dale Jr., Fisher approached every custom with the goal of making it look as though it could have rolled out of the factory that way. He spent countless hours perfecting flow, proportions, and engineering details—especially on his convertible conversions, where he ensured the lines were correct and the folding hood mechanisms worked smoothly. Fisher also developed and fabricated many of his own tools, relying on ingenuity and self-made equipment at a time when the resources available to today’s builders simply didn’t exist.

In a letter written to Michael Ferguson in 2011, Fisher also revealed that his passion for “sports cars” and streamlined coachbuilt shapes predated his custom-car career, listing everything from Austin Healeys to supercharged Auburns, Duesenbergs and Packards as dream material that fueled his early imagination.[1]

Contents

- 1 Early Life and Apprenticeship

- 2 Entry into Custom Car Building

- 3 Rolly Huyshe's FJ Holden Convertible

- 4 The Moonlight Speedster Restoration

- 5 Dale’s Personal FJ Convertible

- 6 The Plymouth and The Pontiac

- 7 Expanding Demand and Influence

- 8 Castle Hill Auto Repairs and the HD Convertible

- 9 Gerry Sweeting's HR Holden Utility

- 10 Transition to Teaching and Blacktown Shop

- 11 Technique and Style

- 12 Retirement and Reflections

- 13 Family and Influence

- 14 Legacy

- 15 Dale Fisher's Cars

- 16 Cars Restyled by Dale Fisher

- 17 References

Early Life and Apprenticeship

Fisher was born in Gundagai, New South Wales, where his fascination with automobiles developed during childhood. In the 1940s, he dreamed of becoming an automotive designer, inspired by the cars he saw on local streets and in magazines.[2]

In 1950, at the age of sixteen, Fisher moved to Sydney to pursue his ambitions. He initially sought a fitter-and-turner apprenticeship but soon realized it would not lead to design work. Determined to work with cars, he turned to panel beating. According to a 1987 Super Street Magazine article by Paul Kelly and Jeff Brown, Fisher visited several of the city’s remaining coachbuilding firms before accepting an apprenticeship with the NRMA (National Roads and Motorists’ Association) . He later recalled that his father hoped he would first “become an engineer” and then move into cars, but Fisher “couldn’t wait,” choosing hands-on panel work over machining repetitive castings.[2]

In his letter to Michael Ferguson, Fisher placed the start of his five-year apprenticeship at the NRMA car repair facility at Pyrmont in 1951, describing it as “the biggest repair shop in the southern hemisphere” at the time. He also recalled living in a boarding house at Haberfield, with his parents were “250 miles away.”[1]

Entry into Custom Car Building

While working at the NRMA, Fisher began experimenting with custom accessories, fender skirts, grilles, and side trims, crafted after hours. These early efforts marked his first steps into custom car building.[2]

The 2011 letter adds a vivid snapshot of Fisher as a young apprentice: on weekend walks along Parramatta Road he studied cars in used-car yards, and at a yard in Ashfield in late 1952 or early 1953 he first spotted a rare Chevrolet Moonlight Speedster, one of the most beautiful bodies he had ever seen.[1]

Fisher singled out details that would later echo in his own custom work: the rear scoops on the scuttle, the dickey seat with its own windscreen, and the “ridge at the back, drawn between the seats,” which he felt foreshadowed the much later Chevrolet Corvette.[1]

Fisher wrote that the Speedster was red-bodied, running red 1939 Chevrolet 16-inch disc wheels in place of the original larger wire wheels, and, crucially, had no folding top or top frame. He borrowed extra money from a school friend to buy it.[1]

He recalled discovering it had a low-ratio differential that made it launch “like a jack rabbit” from traffic lights, something he admits he took advantage of, until he “blew up the diff.” With no spare money to repair it on apprentice wages (while paying rent and paying back the loan), he had to sell the car back to the dealer for about half what he had paid, only two months earlier.[1]

Rolly Huyshe's FJ Holden Convertible

Fisher’s first major custom project came through a friendship with fellow apprentice mechanic Rolly Huyshe. The pair decided to convert a damaged 48-215 (FX) Holden sedan into a convertible, an idea virtually unheard of in Australia at the time.[2]

“We started with only the engine, then we got the subframes, then a bodyshell.” Fisher recalled in 1987. “We welded utility rails underneath and, of course, we didn’t have jack stands or much equipment, we were only kids, so we tipped it on its side, welded on the rails, and tipped it back up again before we cut the roof off.”[2]

During the build, they discovered body flex: the FJ’s subframe skirts were welded to the scuttle, and suspension loads pushed the doors down, so Fisher added a tube along the sill into the fork of the Y-shaped subframe and a triangulated plate and web to stiffen the front and stop the pillars moving.[2]

The result was one of Australia’s earliest Holden convertible conversions. Much of the sheet metal came from scrap, which Fisher painstakingly restored. Though another Sydney panel beater, Barry Cartwright, registered what may have been the first FJ Holden convertible, Fisher’s work helped establish the concept and spread the trend among Sydney enthusiasts. Cartwright’s car reportedly used Vauxhall hood bows, at the time, the only readily available set with near, correct dimensions.[3]

When Rolly’s finished car hit the streets, it drew immediate attention, earning Fisher his first customers for custom work such as dechroming, continental kits, and fender skirts.[2]

The Moonlight Speedster Restoration

By 1957, Fisher had completed his apprenticeship with the NRMA and was working for a new employer in Alexandria. In his 2011 letter, Fisher told Ferguson that while driving to his new employer at Alexandria via Victoria Road, Rozelle, and approaching the Iron Cove bridge, he spotted a 1931 Chevrolet Moonlight Speedster in a car yard. "It was RED and in good original condition, but with NO hubcaps. I put £10 deposit on it and drove back to Beecroft to borrow the balance of £110 from my Aunt. I caught a bus back and paid for it, and drove back to my Aunt’s to pick up my A40. I was late for work that day."[1]

Dale recalled that the 1931 differed from the 1932 Speedster in many ways. "It had louvres in the bonnet sides, in place of the opening doors of the ’32. The bumpers were a different profile in cross-section, the headlamps were a shallower profile, the park lamps were on top of the guards, and it had only 1 cross bar between the headlamps, as distinct from the double bars on the 1932. The car did have a chromed mesh grille guard. However the body was identical to that of the 1932 car."[1]

This became Dale's first of many restorations that followed. "My new boss, Allan Berwick, allowed me to use the workshop after hours and on weekends, so long as I reimbursed him for any consumables. After following months I reworked those mechanical items that required it, and stripped the paint and did a few small dents that it had acquired." Charlie Carney, Allan’s partner, a long time experienced painter, helped and guided Dale in repainting it in RED deluxe, "as close to the original color as we could. Apart from the bumpers, the chrome was in excellent condition. I rechromed the bumpers to match the rest."[1]

Dale told Ferguson that at that time, he did not have any contacts to acquire hub caps. "The closest I could find were on the Renault Fregate. They were of similar size and cross-section, and did not have any badge etc in the centre. I bought 6, including the 2 side mount spares. I could not buy white wall tyres in the size of those on the car, so I painted up walls in a new flexible white paint. This worked well. Over time the road wheel tyres did develop small hair-like cracks in this paint, only visible up close, due to the flex in the tyres. had painted the wire wheels silver."[1]

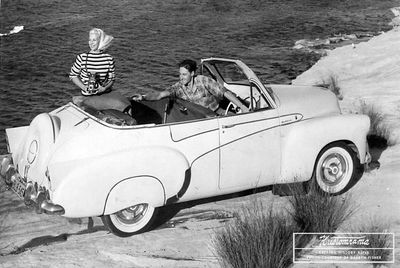

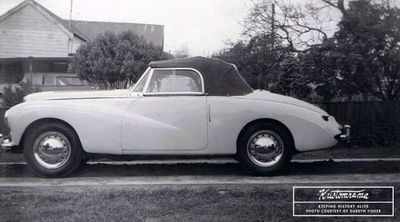

Dale’s Personal FJ Convertible

As Dale's reputation in Sydney grew, he faced a unique challenge. Despite his increasing fame for customizing others' vehicles, Dale himself did not own a custom car. Harvey and Berwick had a contract repairing repossessed cars, and Fisher wrote that one of these deals changed his direction. One day, they brought in a 1956 FJ Holden Special. "It only had slight scratches on the right hand guards, but only about 8,000 miles," he told Ferguson. "The dealer said I could have it for only what was owed on it, which was half what the just released “F.E. Holden Special” cost. This was a chance to buy an almost new car for half price!"[1]

To finance the build, Fisher sold his 1931 Chevrolet Moonlight Speedster and his 1951 Austin A40 to a dealer at Mascot.[1] Working nights and weekends at the shop, he carefully documented materials and paid for everything used, a habit typical of his meticulous approach.[2]

He converted the car to a convertible, added peaked headlamps, fins, and a continental kit, and lead-filled the body seams. Completed in 1958, the FJ embodied Fisher’s emerging aesthetic: a blend of American influence with restrained Australian practicality.[2] After completing the build, Fisher sold it to a dealer at Tempe in 1958 for £1,400—“more than the cost of a new Holden then,” as he put it in his 2011 letter.[1]

The Plymouth and The Pontiac

After completing his work on the FJ Holden, Dale didn't rest on his laurels. His next project was a 1950 Plymouth, a vehicle that, in its original form, was far from what Dale envisioned. True to his nature, Dale transformed this stock car into a custom, and it underwent significant modifications under Dale's skilled hands. He nosed the car, seamlessly leaded the seams, and added hand-made side trims and hubcaps, showcasing his attention to detail and craftsmanship. One of the standout features Dale intended for the Plymouth was a set of Cadillac taillights. However, due to their scarcity in Australia, he had to improvise. Dale's solution was both creative and elegant: he used Zephyr fins, crafted the extensions and surrounds by hand, and fitted them to the Plymouth. The result was a car that, while not featuring the coveted Cadillac lights, exuded a unique and classy charm.[2]

After completing the build, the Plymouth made way for an imported 1950 Pontiac. This car received a series of mild custom touches, reflecting Dale's evolving style. It served as his daily driver until a bold decision in Easter 1960. Dale, driven by his passion, removed the roof of the Pontiac, surprising his pregnant wife, Yvonne. The Pontiac, now roofless, was not exactly the ideal family car, especially with a hospital visit looming. The Pontiac was later adorned with a striking two-tone trim and paint job in yellow and black. This customization further enhanced its appeal, and by the following year, it found a new owner in Newcastle.[2]

Expanding Demand and Influence

By the early 1960s, Fisher had become a sought-after craftsman. The popularity of continental kits, fins, and twin-headlight conversions kept him busy after hours. One memorable customer brought him a brand-new FB Holden directly from the dealership for a twin-headlight conversion, a testament to Fisher’s growing reputation in Sydney’s custom scene.[2]

Castle Hill Auto Repairs and the HD Convertible

Fisher later joined Castle Hill Auto Repairs, where he undertook an ambitious project to convert a wrecked HD Holden wagon into a bright yellow HD convertible. Although the car’s condition was poor, Fisher accepted the challenge. The donor was a flattened wreck retrieved from the base of a cliff at Galston Gorge, with no commercially salvageable panels. The resulting car was featured in Wheels magazine, which mistakenly credited Castle Hill Auto Repairs for Fisher’s earlier custom work. Despite the mix-up, Fisher later acknowledged the misunderstanding as fair given his employment there at the time. The HD convertible was last seen in Sydney in 1970 before being sold to a new owner in Wagga Wagga.[2]

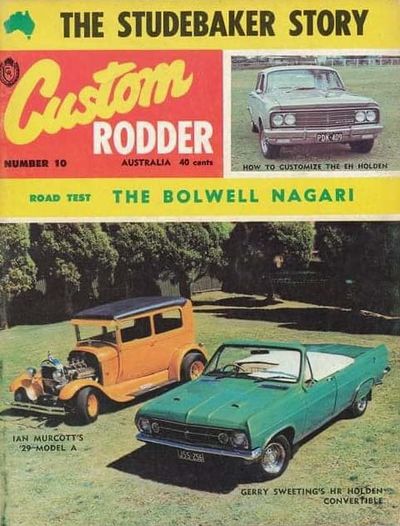

Gerry Sweeting's HR Holden Utility

Among Fisher’s most memorable builds of the 1960s was Gerry Sweeting's HR Holden Utility, radically reworked into a roadster. Using a hacksaw, Fisher removed the roof, rotated the taillights for a Mustang-like look, added a handmade folding roof, and fabricated bonnet scoops. Originally finished in metallic green, the car later changed colors under successive owners but remains a known showpiece and a testament to Fisher’s craftsmanship. A similar HR ute conversion was completed in 1972.[4]

Transition to Teaching and Blacktown Shop

Fisher began teaching part-time at Granville Technical College in 1974, sharing his panel-beating and shaping expertise with apprentices. Two years later, in 1976, he opened his own body shop in Blacktown, focusing on smash repairs but continuing to take on custom work. At Granville, he led pre-apprentices into custom techniques, demonstrating factory-style wheel-arch flares (rather than add-on “blisters”) on projects like a black HQ Premier, and emphasized lead-wiped welds and file-finished metal with no filler.[2]

Technique and Style

Fisher preferred traditional steel construction over the fiberglass add-ons that became fashionable in the 1970s. He frequently built steel replicas of fiberglass panels for customers who insisted on metal. His most notable late-career custom was an XC Falcon two-door convertible, complete with lakes pipes, front air dam, and rear wing, reportedly the first of its kind in Australia.[2]

Fisher critiqued mass-produced plastic bolt-ons as flimsy and look-alike, arguing that true customizing meant one-off parts and individual character. Even his tube-bar grilles were never identical, he varied bevels, added oval end plates or domes, brazed bolts to give hex-ended tubes for extra sparkle, and even incorporated gear teeth to play with light and form. He also linked changing tastes to economics and easy credit: bulk-made parts were cheap and widely available, encouraging fashion over individuality.[2]

Retirement and Reflections

Fisher retired at the end of 1984, closing his Blacktown shop after more than three decades of work. In his 1987 Super Street Magazine interview, he estimated having built or modified several hundred cars: “It’s hard to say; it’d be in the hundreds. My books stopped at two hundred and eighty-something, but that was years ago. I stopped keeping records because there didn’t seem to be any point.”[2]

Reflecting on his career, Fisher expressed some disappointment that custom work in Australia never became a viable full-time occupation: “When I was younger, all I wanted to do was make custom cars, every day from dawn to dark. I think I’ve always been disappointed that there wasn’t enough custom work to make it a full-time business. When I was sixteen, I wanted to be a coachbuilder, something like George Barris, but perhaps not so way-out and exotic: not really bizarre customs, but quality and class bodies, more like the Clenet or Excalibur, not in fibreglass, but in that style.”[2]

Fisher remained modest about his achievements, noting that while American builders had resources and markets for experimental work, Australian customizers worked with limited means and little commercial support.[2]

Family and Influence

In 2019, Fisher’s son Darryn Fisher told Sondre Kvipt of Kustomrama that growing up with his father meant being surrounded by cars and tools: “I was raised into the custom car scene.” For Darryn, cars weren't just a mode of transport. They were a way of life. His dad, Dale, was knee-deep in the custom car game from the 1950s until he hung up his tools. Darryn's first car? A 1962 Studebaker Lark he's had for over four decades. And while he took cues from the classic 1950s leadsleds, being an aircraft engineer added a unique spin to his customizing style. Aussie styles were a bit different from what was seen in the US, mostly because getting your hands on American cars wasn't that easy. But that never stopped the Fishers![4]

Legacy

Fisher’s career spanned the formative decades of Australian custom car culture. His mastery of steel shaping, convertible engineering, and subtle design blended European craftsmanship with American style, helping to define the nation’s unique custom aesthetic. Though he often worked alone and out of modest facilities, his cars, ranging from Holden sedans to American imports, set enduring standards of quality and imagination.

Today, Fisher is remembered as one of the earliest and most prolific independent customizers in Australia’s postwar automotive history.

Dale Fisher's Cars

Dale Fisher's 1931 Chevrolet Moonlight Speedster

Dale Fisher's 1932 Chevrolet Moonlight Speedster

Dale Fisher's 1956 FJ Holden Special

Dale Fisher's 1950 Plymouth

Dale Fisher's 1950 Pontiac

Dale Fisher's 1954 Studebaker

Dale Fisher's 1962 Studebaker GT Hawk

Dale Fisher's 1963 Studebaker Lark

Cars Restyled by Dale Fisher

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Michael Ferguson

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 Super Street Magazine Issue No. 1, 1987

- ↑ The FJ Holden: A Favourite Australian Car By Don Loffler

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Darryn Fisher

Did you enjoy this article?

Kustomrama is an encyclopedia dedicated to preserve, share and protect traditional hot rod and custom car history from all over the world.

- Help us keep history alive. For as little as 2.99 USD a month you can become a monthly supporter. Click here to learn more.

- Subscribe to our free newsletter and receive regular updates and stories from Kustomrama.

- Do you know someone who would enjoy this article? Click here to forward it.

Can you help us make this article better?

Please get in touch with us at mail@kustomrama.com if you have additional information or photos to share about Dale Fisher.

This article was made possible by:

SunTec Auto Glass - Auto Glass Services on Vintage and Classic Cars

Finding a replacement windshield, back or side glass can be a difficult task when restoring your vintage or custom classic car. It doesn't have to be though now with auto glass specialist companies like www.suntecautoglass.com. They can source OEM or OEM-equivalent glass for older makes/models; which will ensure a proper fit every time. Check them out for more details!

Do you want to see your company here? Click here for more info about how you can advertise your business on Kustomrama.